Inside this issue:

An extremely stable GENIUS bill

There is no such thing as a dollar

If it quacks like a bank account …

America is a club promoter

Winners love it when a winner-takes-all

The stable future and what to do about it

An extremely stable GENIUS bill

On July 18th the U.S. became the first major jurisdiction to formalize a regulatory framework for stablecoins, as the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins act (or GENIUS act) became law.1

The bill creates a new legal category for payment stablecoins that is distinct from securities or commodities. Qualified stablecoin issuers are required to be federally licensed or state chartered institutions, be 1:1 backed with a combination of U.S. dollars/treasuries and must comply with the Bank Secrecy Act — meaning they need to support court ordered freezing or confiscation of assets. The actual requirements of the legislation are scheduled to roll out starting in November of 2026, with new regulations going live in stages through 2028.

The GENIUS act was relatively non-controversial by modern standards — it passed with a comfortably bipartisan margin of 68-30 in the Senate. Bank legislation is relatively dry compared to other, more lurid news stories so coverage was limited. But to those paying attention, the formalization of stablecoins represents a monumental turning point in the history of the dollar.

I think it is worth your time to understand.

There is no such thing as a dollar

The most useful thing about dollars is that they are interchangeable — the dollars I give you are worth the same as the dollars you give me, and so on. The strangest thing about dollars is that if you look closely they turn out not to be interchangeable at all. You can’t use bank dollars to buy drugs and you can’t use paper dollars to buy a house. You can transform bank dollars into paper dollars (or vice versa) but they aren’t quite the same thing.

There are a lot of different kinds of dollars. Paper money is not the same as Amazon refund credit is not the same as a Paypal balance is not the same as a master account with the Federal Reserve. There are also other assets that we don’t usually think of as dollars, but work in a similar way — any dollar-denominated debt instruments for example (including US Treasuries) are essentially future dollars attached to some counterparty risk.

All of these instruments are basically "dollars" where the scare quotes represent the specific constraints imposed by that particular system. There is no platonic dollar. There are no "real" dollars in the same way there are no "real" inches — dollars are a measurement, not a material. When we talk about the strength of the dollar what we’re really talking about is how much wealth the world is using dollars to measure.

If it quacks like a bank account …

Stablecoins are a new kind of "dollar" — specifically they are a new kind of bank account. You send some "dollars" to the stablecoin bank, the stablecoin bank updates their ledger to credit your account with some number of dollars. Subject to whatever rules the stablecoin bank imposes you can transfer your dollar credits to other accounts within the network or withdraw them to other dollar systems.2

If you strip the word 'stablecoin' out of that description, you’re just describing a traditional bank account. But there are a few reasons people are uncomfortable calling stablecoins bank accounts in spite of the similarities.

First, bank accounts in U.S. banks are insured under FDIC and stablecoins are not (at least today). The reserve requirements and bankruptcy rules in the GENIUS act are designed to protect consumers from insolvency risk, but the government does not directly insure stablecoin accounts. That makes stablecoins both less safe (because stablecoin users are exposed to the credit risk of the issuing bank) and less interchangeable (because credit risks are different for different banks).

Second, opening a bank account in a U.S. bank requires submitting a lot of paperwork and identification material and U.S. banks are subject to strict "know your customer" laws that require banks to track and report on who is sending money to whom using their banking network. In contrast, creating a new stablecoin account only requires doing some anonymous math and stablecoin banks generally know almost nothing about their customers’ identities.3

Third, stablecoins (at least the ones legally codified in the GENIUS act) are not allowed to pay interest, where traditional bank accounts are. Given the low interest rates paid by bank accounts today this may not seem important but it turns out to be a pretty critical detail.

By combining these three things: no FDIC insurance, no interest and no KYC/AML checks, stablecoins act like a "low-powered" bank account, sometimes called a narrow bank. That trade-off isn’t all that exciting for customers who have access to traditional FDIC insured U.S. bank accounts, but there are still an estimated ~1.4 billion unbanked people in the world today. Because stablecoins skip the expensive KYC/AML checks, they can reach customers with much smaller accounts in the economies where customer identification is much harder to do.

Traditional bank accounts are safe but expensive to open. Most of the world’s population simply does not have enough wealth to making opening an account profitable for the bank. A stablecoin address is essentially a cheap, disposable bank account that can be used more flexibly than a traditional account.

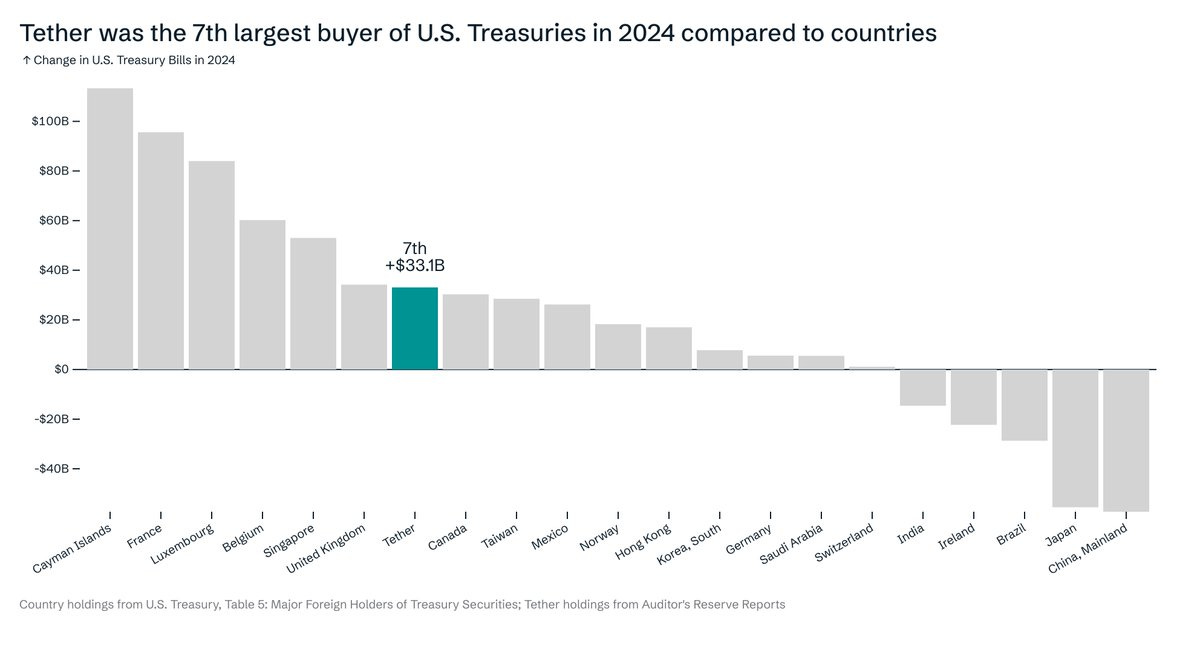

Stablecoins are also staggeringly profitable. The largest stablecoin today is Tether, with ~400M users and a market cap of ~$163B.4 That’s still relatively small compared to the estimated ~1.4 billion people still unbanked worldwide, but it’s large enough to make Tether the 7th largest buyer of U.S. Treasuries, just ahead of Canada and just behind the United Kingdom. Tether just reported Q2/2025 profits of ~$4.9 billion, will only ~200 employees.5

Buying billions of dollars worth of treasuries with customer money and keeping all the interest for yourself is an incredible business model. One way to think about stablecoins is that they are a way of renting out U.S. banking services to the global poor, with the profit coming from all the interest you never pay them. From America’s perspective, unlocking billions of dollars of new demand for treasuries lowers the cost of government debt and makes it easier to keep spending.

Calling stablecoins bank accounts raises all sorts of uncomfortable questions about why they don’t have to pay interest or meet onerous surveillance requirements, so is more politically expedient to simply describe them as something wholly new and innovative: an unprecedented new advance in the world of financial technology! But stablecoins are to bank accounts as Ubers are to taxis. The real innovation is regulatory arbitrage.

Stablecoin is a marketing term. They’re just bank accounts.6

America is a club promoter

America spends lots of money and the money America spends is mostly dollars, so it is good for America when lots of people want to use dollars to measure their wealth. When lots of people want present-day dollars they become valuable and it gets easier for America to buy expensive things without taking on debt. When lots of people want future dollars, Treasuries become valuable/interest rates fall and it becomes cheaper for America to take on debt when buying expensive things.

The strength of the dollar is also the source of much of America’s soft power. American sanctions matter mostly because they make it harder for sanctioned nations to get and spend dollars. American banking laws matter because U.S. regulated banks have access to the most (and best) dollars.7

There is a tension to these benefits. When more people use dollars to trade, you can impose stricter requirements on dollar traders, but stricter requirements also increase the risk that people will stop using dollars to trade. When more people use dollars to save, the government can create (and spend) more dollars — but the more dollars the government creates to fund spending, the greater the risk people will stop using dollars to save.

The American dollar is like an exclusive club where America sets the dress code and the price of entry. That’s a lot of power — but to maintain that power the club needs to stay desirable. It needs to offer the services people expect at a price they find reasonable, otherwise they’ll leave and a new club will become popular instead. As of 2022 roughly ~40-75% of all U.S. dollars were held outside the U.S. — so Americans might own the club, but most of its members are global.

Stablecoins are a way of welcoming a new and lucrative demographic of people into the dollar club. America relinquishes some of the control it has traditionally demanded over bank accounts in order to coax a new category of wealth into the dollar hegemony — like opening a new section of the dollar club with a relaxed dress code and fewer ID checks.

Winners love it when a winner-takes-all

Another important distinction between stablecoins and traditional U.S. bank accounts is that anyone can transfer dollars between bank accounts but only special banking partners can withdraw stablecoins outside the network. For ordinary people to get their dollars out of a stablecoin network they have to sell them to someone who wants that kind of stablecoin, usually at a discount. That’s why the trading price for stablecoins tends to hang out just below $1 instead of exactly at $1. The spread represents how much people are paying to exit (or enter) the network.

That means that transfers within the stablecoin network are much cheaper than transfers into or out of the stablecoin network. Withdrawing dollars from a stablecoin network is less like transferring dollars between U.S. banks and more like selling dollars for another currency on the ForEx market. It’s expensive and unpredictable, especially at large scale. That encourages people to transact within the network (where it is cheaper) and to join the largest network available (so they can transact cheaply with the most people).

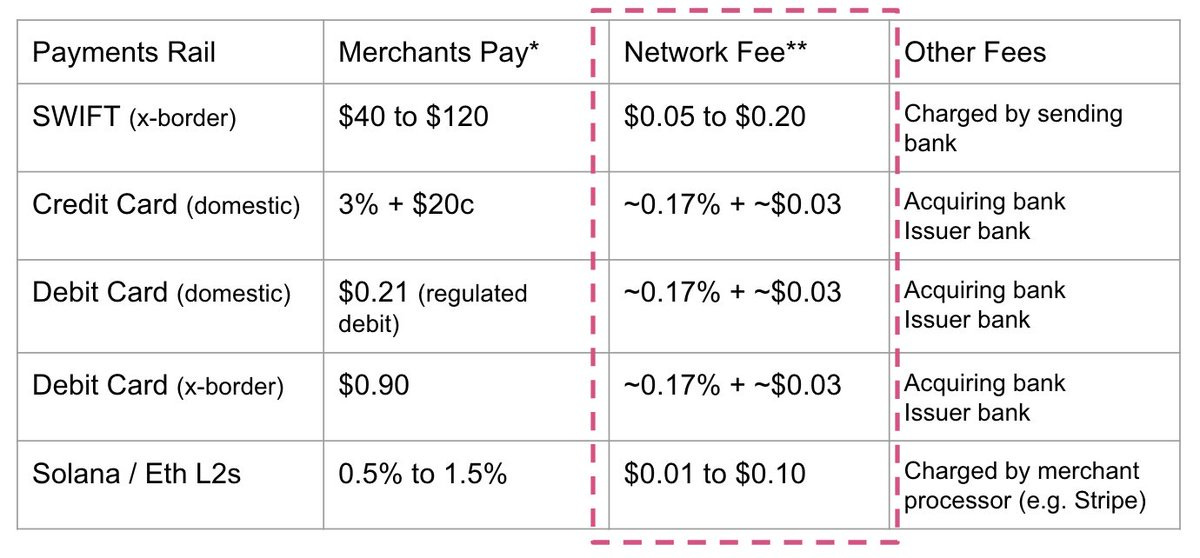

In that sense, stablecoin networks aren’t really competing with individual banks, so much as they are competing with the entire U.S. banking network. Stablecoins are cheaper and more private than traditional bank accounts and over time they will likely acquire a similar degree of consumer trust and the ability to pay interest. That will be good news for stablecoin users and for U.S. dollar dominance — and bad news for traditional retail banks and credit card networks.

Most of the cost of traditional payment networks like SWIFT, VISA or PayPal is managing risk. Stablecoin ledgers undercut that cost by managing risk through cryptography instead of expensive trust brokers. That makes them fundamentally cheaper than traditional networks even without any regulatory arbitrage.

It won’t happen overnight, but on a long enough timeline stablecoins will probably replace traditional bank accounts and payment networks for most retail customers. I’m honestly surprised credit card lobbyists aren’t more concerned.

The more immediate impact of stablecoins will be on weaker currencies. Any country where there is significant informal demand for dollars as an alternative to the local currency is likely to experience a collapse. A stablecoin may seem high-risk when compared to an FDIC insured U.S. bank account, but compared to a rapidly inflating local currency or onerous local banking requirements it may seem like a chance to shed risk and shelter wealth in (relative) safety.

For the weakest currencies (the Nigerian naira, the Lebanese pound, the Venezuelan bolívar, etc) this will accelerate the existing currency collapse / dollarization of the local economies. That will probably be good for the locals who will be able to protect their savings from inflation — but it will weaken many governments’ ability to raise funds or impose capital controls and it will kill some currencies off entirely. The dollar will continue to swallow smaller economies as it grows.

The stable future and what to do about it

I suspect the passage of the GENIUS act means the following things:

Stablecoins will eventually replace traditional bank accounts / payment networks

The global dominance of the U.S. Dollar will continue to accelerate8

Smaller / weaker global currencies are likely to weaken and collapse

Banking surveillance and KYC / AML regulations will be renegotiated

In the short run this will weaken surveillance (as stablecoins use regulatory arbitrage to undercut traditional payment networks)

In the long run it will greatly increase surveillance (as America takes advantage of the greater demand for dollar access to impose stricter surveillance and controls)

I don’t know that there is anything obvious we can do to position ourselves for these particular predictions. Apply for a job at Tether? Sell your bolívars? Finish up any financial crimes before the new surveillance regime comes online?9

The safest thing to do is to subscribe to Something Interesting.

For the purposes of this essay I will be focusing on reserve-based stablecoins like Tether or USDC rather than misguided attempts to simulate stability like DAI or Terra/Luna.

In practice most stablecoins today only offer dollar withdrawal to their banking partners, not to their retail customers.

Issuers are still required to perform KYC checks on the dollars that come in and out of their network, but not on the addresses within the network. One way to think about stablecoins is that they are banks for people who would like to evade bank secrecy laws.

An average balance of ~$407/account, for those keeping score at home.

An average profit of ~$65M/employee, for those keeping score at home.

A lot of people are very eager to draw analogies between stablecoins and the private money issued by 'wildcat banks' in the 1800s. I don’t think that’s completely off-base, but I don’t love it as a comparison for a variety of reasons. First, stablecoins are ledgers not tokens. Banks can remotely freeze or seize stablecoin balances in a way that cannot not be done with physically issued private bank money. The trust model for a stablecoin is closer to a bank account than it is to a private bank note. Second, people have a lot of weird misguided beliefs about the wildcat banking era that are basically just a distraction from understanding stablecoins today.

In general what kind of dollar is 'best' depends on what you’re trying to do with it, but for the purposes of high-finance the 'best' dollars are the ones stored in master accounts at the Federal Reserve.

Assuming J. Powell can stop any fat orange pedophiles from fucking it up for everyone.

This is not legal advice.

Your analogy of America as a club promoter dovetails nicely with my view of stablecoins as a softer extension of the military-industrial complex. Instead of boots on the ground, we now have blockchain rails projecting influence. The GENIUS Act seems less about innovation and more about securing a first-mover advantage in this new phase of economic diplomacy.

https://divistockchronicles.substack.com/p/stablecoins-the-next-evolution-of

Appreciate the clarity and wit throughout—especially the “Uber to taxis” comparison. Spot on.

Finally made it back to this bookmark :) loved reading this